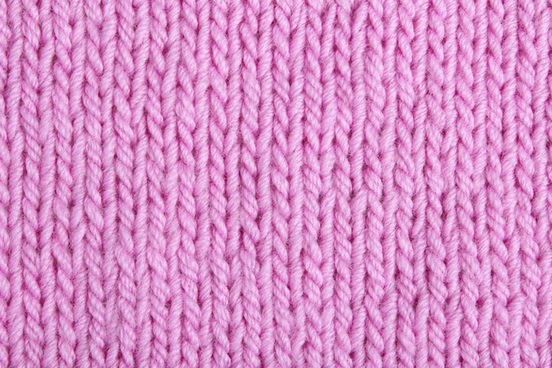

Stockinette

(Note: this is a sequel. Click here to read our first knitting list)

Though knitting is only made up of two stitches (knit and purl) the combination of those creates a variety of patterns and textures. There are two such textures that are considered the building blocks of most knitwear, and one is stockinette stitch.

First, a clarification: stockinette is not a stitch as such, like knit and purl are, but a pattern created by repeating knit and purl stitches in a particular way. Stockinette stitch is what we think of as “regular” knitting: it is made by alternating knit and purl rows so that one side of the fabric shows interlocking loops (knitting) and the other side shows rows of short horizontal loops (purling).

The word stockinette first shows up in written prose in the late 1700s as an alternation of the phrase stocking net. Net is an earlier word for knit, and stocking net was just that: a type of knitting that was very elastic and used for items that needed to stretch and retain their shape—like stockings. Our earliest uses of the word, going back to the 1700s, don’t refer to the stitch itself, but to the fabric produced by stockinette stitch:

During this little colloquy, Mr. Kittington, in stockinet pantaloons and pumps—time half-past eight in the morning—stood fiddle in hand naturally looking particularly awkward.

— The New Monthly Magazine, 1837

Nowadays when knitters talk about stockinette stitch, they are referring not just to the pattern, but to the combination of stitches used to create that pattern: knit one row, purl the next. Stockinette wasn’t applied to the knitting stitch until the middle of the 20th century.

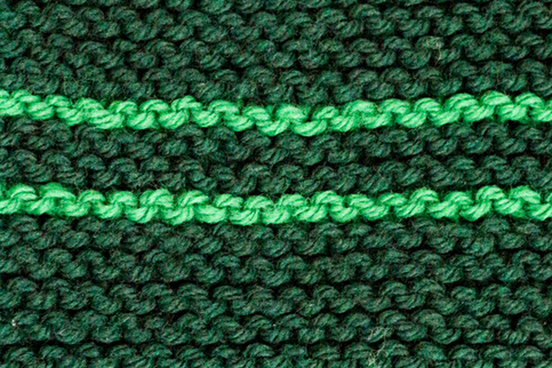

Garter

We said that stockinette stitch was one of two foundational textures in knitting. The other one is called garter stitch. Like stockinette stitch, garter stitch is not an individual stitch: it is the stretchy and corrugated fabric that results when you knit every row.

Garter is a much older word than stockinette, going back to the 1300s. It originally referred to a band of fabric tied around the leg to keep stockings up. Elastic is a modern invention, as are tights and pantyhose, and even the most cleverly knitted socks will slide down your leg without a little bit of help. The name for the stitch was taken from the name for these bands—supposedly garters were knit in garter stitch (which is much more elastic than stockinette stitch).

The earliest written use we currently have for garter stitch comes from an 1840 book of knitting, netting, and crochet patterns by the Scottish knitter and businesswoman, Jane Gaugain. Gaugain’s books were some of the earliest commercial knitting and crocheting books in print and were very successful: The Lady's Assistant racked up 22 editions. The very first instruction Gaugain gives in her knitting book is for garter stitch.

Cable

There’s a lot you can do with two stitches. Not only is intricate colorwork done with just the knit and purl stitches, but those two stitches also produce sweaters covered in what looks like knitted ribbon. Those ribbon motifs are known as cables.

Cable first appeared in English writing in the late 1200s, where it referred to a strong rope. In a few hundred years, cable came to be applied to ropes made from materials slightly stronger than hemp or linen—the word was used in particular of the iron chains used to tether ships to their anchors. Cable began to be differentiated from rope: one was made of metal, and the other not. Nowadays, we associate cable with everything from the large-diameter metal ropes that support bridges to bundles of thin copper wire that deliver television signals to our homes. We even began using cable to refer to the television shows delivered to our living rooms and dens by the physical cable.

Rope is not knitted—it’s woven. But if you’ve had the opportunity to pull apart a cable, you’ll begin to see why the repetitive and raised knitting patterns called cabling gained the sobriquet.

While there are many knitting patterns back to the late 1800s that feature cables, they are inextricably linked to a style of fisherman’s sweater associated with the Aran Islands in Ireland. Aran sweaters are usually heavily cabled, using many different cable patterns at once. The widely dispersed mythology surrounding Aran sweaters is that the cables were tied to particular clans—so much so that the sweaters themselves were supposedly used to identify the bodies of fisherman who had drowned and later washed ashore. This is, however, false: knitwear designer and historian Kate Davies gives a thorough explanation as to where the myths came from on her blog.

Lace

If cabling creates a fabric whose texture is multidimensional, then lace is its opposite. It creates texture using negative space.

Lace is a fabric notable for all the intentionally placed holes in it, and knitters have been creating lace for centuries. The word, however, is older than the art form. When lace first appeared in English writing in the 14th century, it was used to refer to a net or a snare—it came into English via French, and is ultimately from the Latin word that means “snare.” (The same Latin word gave us lasso). Almost immediately, the word was applied to cords or ties that drew something closed, like a snare closing around prey. This is the lace we associate with shoes, and the lace that is associated with corsets and bodices.

By the time of Henry VIII, lace had come to refer to ornamental cording and braids used to trim men’s coats:

His persone was apparelled in a coate of purple velvet, somewhat made lyke a rocke [rook], all over enbrodered with flatte golde of Dammaske with small lace myxed betwene of the same golde...

— Edward Hall, The vnion of the two noble and illustre famelies of Lancastre [and] Yorke, 1548

Sartorial ornamentation was a big deal in the Tudor court, and one type of sewn ornamentation, called cutwork embroidery, became the foundation for the frills we now consider lace. Cutwork embroidery is a technique where holes are cut into fabric and then kept from tearing or fraying by being embroidered around. In the 16th century, the cutting was removed from the equation altogether: lacemakers found a way to make, with needles, both the airy ground and the embroidered ornamentation at the same time. This new style of ornamentation was called lace, from the idea of weaving decorative threads in and out of a lace pattern, as one would lace up shoes.

And though this is a list of knitting words, lace can be made in a variety of ways: by crochet, tatting, or using bobbins, for example.

Angora and Mohair

Lots of knitters like wool, but there’s a variety of wools to choose from, and not all of them are sheep-based. Take angora. As we use it today, it is the eponymous name for the wool harvested from the Angora rabbit. Angora is very fine and very warm, and because of the properties of the wool, yarn made with angora tends to have a characteristic halo of soft, nose-tickling fibers. The word angora derives ultimately from the place where the rabbit breed was thought to originate: Ankara, Turkey.

But when angora first appeared in English writing at the beginning of the 1810s, it didn’t just refer to the wool from Angora rabbits. It referred to the wool from Angora rabbits or Angora goats—also from Ankara. This caused some confusion, as the wool from Angora goats is nothing like the wool from Angora rabbits: where angora (rabbit) is fine, soft, and flyaway, angora (goat) is long, shiny, and not always soft. To make matters worse, the wool from Angora goats already had a name that had been established in English for hundreds of years: mohair. Some 19th-century citations for angora only compound the confusion:

Mohair yarn is employed largely in Paris, Nismes, Lyons, and Germany, for the manufacture of laces, which are substituted for the silk-lace fabrics of Valenciennes and Chantilly. The shawls frequently spoken of as made of Angora wool are of a lace texture and do not correspond to the Cashmere or Indian shawls. The shawls known as llama shawls are made of mohair.

— John Hayes, The Angora Goat: Its Origin, Culture, and Products, 1882

It is confusing to many that the wool from the Angora rabbit is angora while the wool from the Angora goat is mohair, but we might be able to blame that on Italian cloth merchants. Mohair comes from the Arabic word mukhayyar, which means “choice.” It’s probable that the fabric sold by Arabic speakers to Italian cloth merchants was called mukhayyar to represent the quality of the cloth or the fiber used to make it (“choice”); it’s also probable that Italian merchants misapprehended the meaning of mukhayyar and assumed it was the name of the long, lustrous fiber used to make the fabric. Regardless, through some sound and spelling changes, mukhayyar came into English through Italian and became mohair. The later angora, despite its initial confusion, is now used primarily of wool from Angora rabbits.

Worsted

Yarn comes in a variety of weights, by which yarn manufacturers really mean “gauges.” Lace-weight yarn is quite thin, and bulky-weight yarn is quite thick. In between lace- and bulky- are a number of other weights with unintuitive names, like worsted.

Worsted-weight yarn is, according to the standards published by the Craft Yarn Council, a medium-weight yarn that knits up at 4 or 5 stitches per inch using a 4.5–5.5mm needle. But as common as worsted-weight yarn is, it’s not always worsted. Worsted as used of a weight of yarn is a modern invention, though yarns have been worsted since the 13th century.

The vast majority of yarns are spun, and the way the fiber is prepared for spinning as well as the spinning itself affects the final product. As far back as the 13th century, we have evidence of the word worsted used for a fabric made from wool whose fibers had been combed in preparation for spinning. Combing wool rearranges the fibers so they lay parallel to one another; when spun, those parallel fibers form a tight, smooth, compact yarn. This preparation and style of spinning was called worsted after the Worstead parish in Norfolk, England, where this style of spinning was evidently popular. But worsted spinning isn't the only game in town: wool can also be spun woollen. In woollen spinning, the fibers are not aligned parallel to each other, and the resulting yarn is looser, fuzzier, and airier.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, cloth production was mechanized. The power looms used to create cloth during the Industrial Revolution were geared more for worsted-spun yarn, since it’s stronger, smoother, and less prone to breaking under tension than woollen-spun yarn is. The demand for worsted-spun yarn increased, and spinning mills complied. Mechanized spinning and weaving technology improved, and nowadays mills can produce true woollen-spun yarns. But sometime during the early 20th century, the word worsted began to be applied to a weight of yarn, not just a style of yarn:

The yarn best adapted for sweaters of medium weight is a 4-ply yarn known as “Knitting Worsted” or “Scotch Worsted.”

—Stuart Louchheim, “Hand Knitting Yarns” in Commercial America, June 1923

It's likely that these worsted yarns were, in fact, worsted-spun. But mills are most profitable when they can produce a stable, even yarn in quantity, and with minimal fussing with equipment. That meant that those 4-ply worsted-spun yarns mentioned by Louchheim were all roughly the same weight. Mills may have called them worsted after the process, but marketers and consumers soon associated worsted with a medium-weight yarn made by any spinning process.

Tink

All good things must come to an end—and that includes knitting. It is inevitable that eventually the knitter will make a mistake in a pattern and need to correct it. There are two options open to them: stuff the project in the bottom of a bag and forget about it, or rip it out.

Ripping out knitting is the act of taking it off the needles and pulling on the yarn to unravel the knitted item. (This is also called frogging.) But not all knitted items can stand to be ripped out. That angora yarn with the lovely halo catches on itself and snarls; that cashmere may pull apart if you yank too hard; there’s no way you can rip back a few rows of your cabled sweater or lace shawl and ever hope to put the dang thing back on the needles properly. And what about the momentary lapses in attention that result in an error just a few stitches back?

In those cases, there is tinking. It is the act of unknitting an item. Rather than pulling the fabric off the needles, each stitch is picked apart using the needles and slipped back into its pre-knit position. The action is explained in the etymology: tink is the word knit backwards.

The word gained written use in the early 2000s:

To tink means you keep the stitches on the knitting needles and then one stitch at a time, un-knit them. (The word tink comes from the word knit spelled backwards.)

— Bulletin of the International Old Lacers, Incorporated, 2001

though some of our other evidence, including transcripts from a sociological study on knitting groups, makes it clear that tink was in spoken use among knitters for some time before that. In spite of the fact that it’s been around for almost two decades in the knitting community, tink still often shows up in print with a gloss of what it means, as well as a sentence or two on its etymology. That means it's not yet entered into our dictionaries.